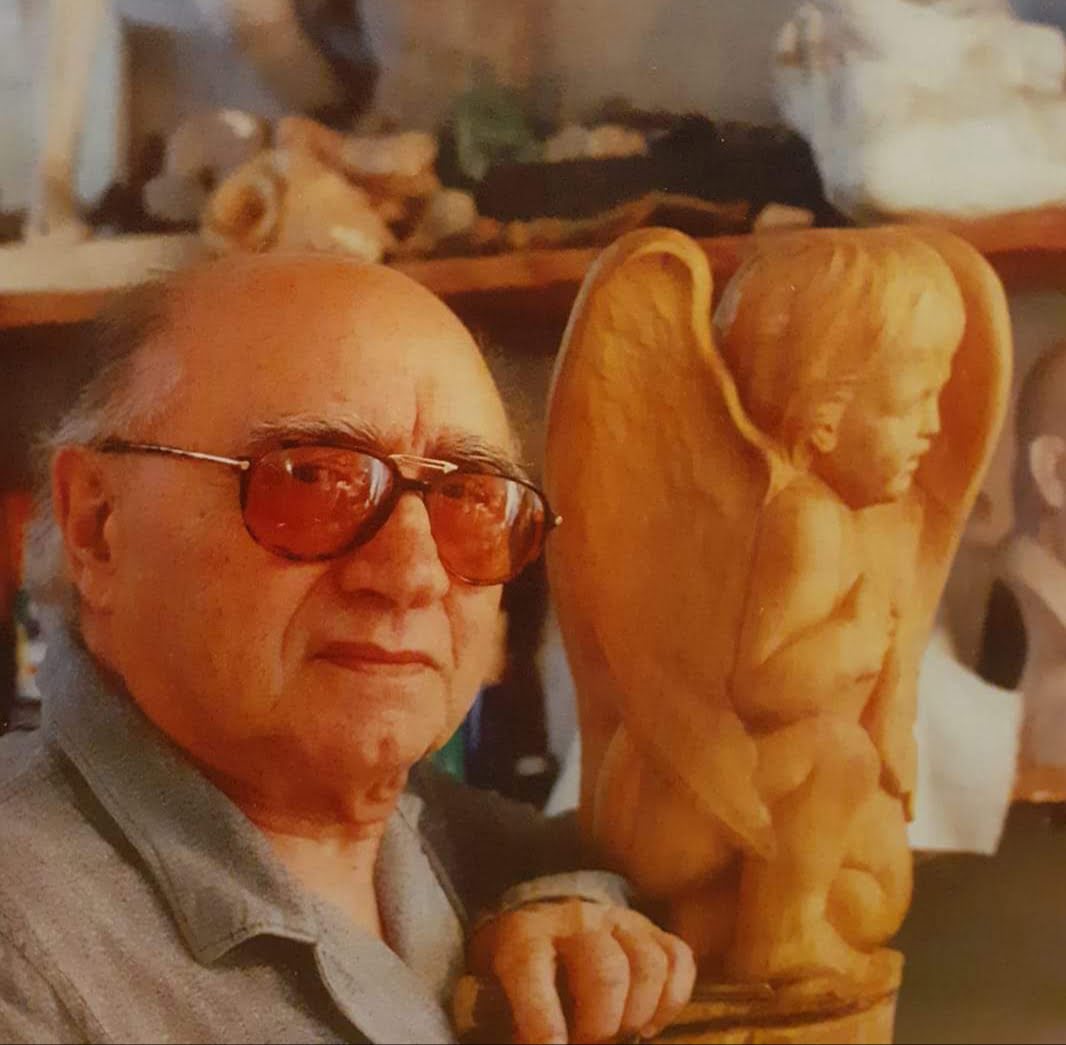

Samuel Bugeja - The Person

Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 | Page 4 |

It was the mid Sixties of the last century. Samuel Bugeja was riding high on restoration commissions with the Metropolitan Cathedral - fully backed by the then Archbishop Michael Gonzi who relied on the advice and collaboration of the top Italian restorer and esteemed Head of the Centro del Restauro in Rome. Malta, in turn, was tasting its acquired Independence from Britain - though many still looked up at the Colonial power for material comfort. In spite of being busy with his restoration, my father was still an artist at heart and missed the time required to create his art from trunks of wood he loved so much with a passion. His days, however, were mostly spent teaching art at secondary level to the ambitious up-coming young generation of the post-war baby boom. On top of that he conducted daily carving and modelling classes at the School of Art carving classes. In spite of his private restoration work load, he still managed to find the creative windows he craved for. Invariably, those took place on Sundays.

Though this life-style suited him fine, my father was ever becoming more insular than ever. The art circle he used to frequent so much during his formative years at the School of Art had long diluted to a few artists whilst the ones that had returned from studies abroad were ever so enthusiastic on the modern movement. Nuclei of diverse movements were forming and a new dynamic scenario evolving. My father was well aware of the upheaval art was taking. Being a pedigree classical artist, he could never betray his committed form in art. At the same time, he had to give his creativity the contemporaneity that any artist requires to transmit to facilitate communication with the dynamic artistic circle that was evolving.

It was in that period that the Society for Arts, Manufacture and Commerce decided to organise a unique opportunity for all Maltese artists to exhibit a well marketed event in London. Samuel just could not miss the bus. He had already put his creativity at work in 1956 with a deeply spiritual facial introspection of a cowled monk that was the exhibit targeted for extremely high acclamation by Eric Newton, the British renowned art critic, artist, author of art books and broadcaster. Newton was, amongst other high profile positions, art critic of The Times of London for a number of years besides lecturing on Modern Art. My father, having considered Eric Newton´s very positive critique, as duly published in the media at the time, took the drift. Convinced he was on the right track, he went on to create a mother and child out of a delicately balanced naturally curving wooden trunk. It had all the spirituality, linear balance, expression and elegance that would have enthused Eric Newton. Yes, that work would do Samuel justice in London for the Society of Arts, Manufacture and Commerce exhibition of all the top Maltese artists.

However, there was one problem. All works had to have a price tag. My father never wanted to part with any of his works of art. How could he do an exception with this? Never. But the Society needed to cover its expenses and this could only take place if it gets its commission from the sale of the works of art. Besides, there had to be an insurance value in case of any mishaps during their travels. It was Carmel Cuschieri and Paul Asciaq, the highest incumbents of the Society and both colleagues of my father at St Joseph Secondary Technical School, Paola, who personally persuaded him to give it a price.

At home, my father discussed it with my mother Nellie in my presence. I was in my mid-teens then but had been doing support work to my father for at least 5 years because I loved his work. It was agreed that the price tag was to be high enough to put off any potential buyer. After sounding us out, my father decided on a value in Sterling. An astronomical sum that was equivalent to much more than two years’ salary of Master at the Education Department. We had our mind at rest that the Mother and Child would not be sold. Considering that all other works of art for the exhibition were price tagged by their own artists well below even the half-way mark of Samuel’s Mother and Child, the assumption was understood to be in order.

One can never imagine what happened at the opening of the exhibition. We came to know about it in the most sensational way - the media. In fact, the day after the exhibition opening a news feature on the Times of Malta announced the sale including a good photo of the buyer – the President of The Friends of Malta, Lindsey-Finn - pointing his forefinger at the Mother and Child and surrounded by the Society’s officials. My father was at cross minds what to do next.

Not endorsing the sale would be a big set-back to the organising Society. Parting from the Mother and Child would be heart-breaking. It was a situation where compromises could not feature. Eventually the statue became the possession of Lindsey-Finn after he came to Malta and shook hands with my father as the author and creator of the statue. However, the whole issue had left my father with mixed feelings regarding exhibitions where commercial interests are concerned. He became even more cautious when such participations had to take place.

It is my belief that the Sixties and early Seventies characterised Samuel Bugeja’s strongest expressions in the spirit of the modern idiom in wood sculpture. His 2-year scholarship studies divided between the Leicester School of Art in Britain (1948/9) and the Centro del Restauro in Rome, Italy (1955/6), were a catalyst to release his own interpretation of figurative art in the modern idiom. The carving technique developed into a series of spontaneous, individually identifiable, fresh cuts. The collective carvings did not detract from the digestible reading of the figurative form – it just made it look so naturally coming direct from the carver’s own hands and a distinct departure from the conventional figurative replication of human form. One can even say that Samuel Bugeja created his form of modern figurative carving in the equivalent impressionist style to modern painting. Another modern idiom also became evident. It was the focus he created just on that part of the figure that the artist elected to highlight. This was achieved by having the surrounding surfaces treated in rugged carved texturing. The end result was one of capturing powerful human expressions coming across forcefully and freshly carved. It was like assisted camera zooming leaving the surround blurred.

My father manifested his newly acquired expressive art by applying his art on diverse themes. These themes varied from the female maternity with child, introspection into the future, the Divine Comedy by Dante and figurative representations of normal people in the course of their work – such as the olive vendor and the ballerina. The theme of his creations in wood got their first inspiration from the shape of the tree trunk. Being Y shaped or curved or convoluted – depending on how nature endowed it – was in itself the origin. The figure came as a direct consequence. My father was constantly seeking excitingly shaped trunks walking or travelling in the countryside he was brought up with – that outside his village of Rabat which is blessed by nature in its various valleys, afforestations and fertile field terraces.

Spurred by this momentum, Samuel Bugeja staged two important solo exhibitions. The first was that in January 1969 at the Cathedral Museum in Mdina. It manifested his modern style in wood carving creating art on various figurative themes. However The Divine Comedy in wood took pride of place. It had been selected for notable mention by the selection Committee of the Dante Alighieri monument presided by Prof. Raffaele Causa. My father had bitter experiences of these competitions because of dubious selection magnanimity. So, in a show of disappointment to the sometimes vitiated selection process he would exhibit his proposal ‘outside the competition’. Invariably, the selection Committee would have no option but to give pride of praise to Samuel Bugeja’s work whilst stating that his work could not be selected because it was ‘outside the competition’. The mistrust my father harboured to certain establishments was manifested by this gesture which hardly softened matters. In the long run it made my father to withdraw further and take a more reserved stance and hardly attending any social events at all.

The second solo exhibition took place three years later in 1972 at the Malta National Museum, Valletta. This time, a particularly moving and expressive Mother and Child took pride of place. At that time I was abroad on post-graduate studies. My gut feeling at the time was that, as far as solo exhibitions were concerned it came too close to the one of 1969 for it to have the desired effect. However, I was not close to events at the time to know what my father had in mind then. What can be stated is that the Minister Paul Xuereb that inaugurated the exhibition (he eventually became President of the Republic) hailed from Rabat, the same locality of my father’s upbringing and they knew each other quite well.