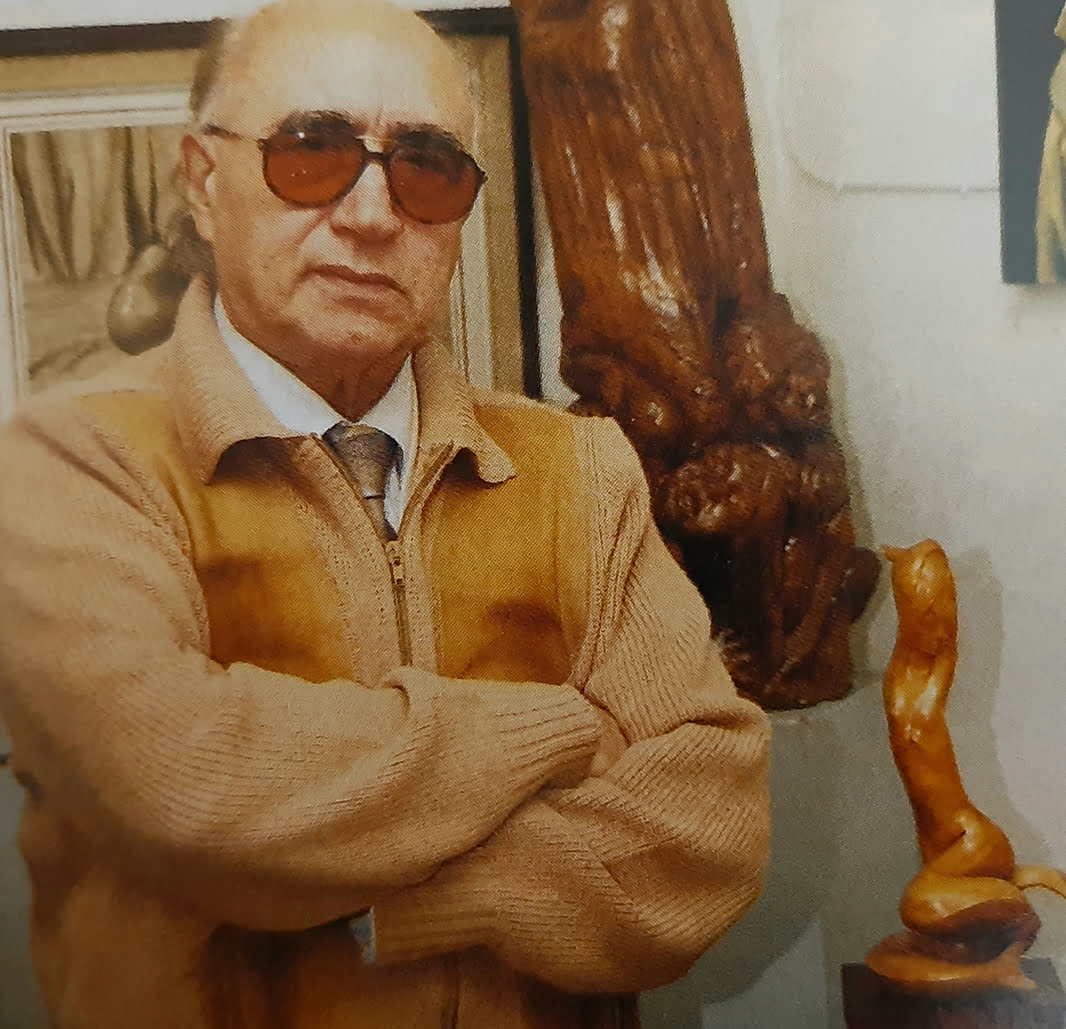

Samuel Bugeja - The Person

Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 | Page 4 |

Though, to a much lesser extent, Samuel Bugeja kept the modern trait throughout his later art work, his art gradually tended back to his classical origins, including the established themes of spirituality and maternity. This passage was aided and abetted by a relatively early retirement in 1978 when he was 58 years of age, just 3 years short of full service and in a Head Master role in the public service. The retirement occurred at a stage when his artistic guidance towards greater empowerment and participation of students in life was bearing fruition.

The Government policy at the time, particularly that in the Ministry of Education led by Agatha Barbara, promoted art work by students towards public events such as Carnival. Though my father was not keen of such mundane manifestations, he successfully helped young secondary students to produce prodigious masquerades and imaginatively colourful attire. But the feather in his cap was the guidance to the winning entry of the new National Emblem. Government´s wish was that a number of different submissions be sought from young students according to set compositional items. These included what were recognised national symbols such as the luzzu, the prickly pear and the farmer´s basic working tool all under the warmth of a bright sun. Though the final composition had nothing similar to the traditional heralding symbolism characterising National emblems, the selected design became accepted for a good number of years until its reversion to conventional designs.

It was during this period of somewhat hectic activity that my father passed through a withdrawal phase. Was the exposure too much? Was it the dynamics of having to handle so many people simultaneously? Was it the rapidly changing scenario triggered by policies and their fast-track implementation? Was this newly-imposed life-style taking him on a path radically alien to his intrinsic artistic creations? What is certain is that my father entered a rather sad mood which precluded him from pursuing his educational career any further. His mind kept ruminating to those totally different achievements to the new form of educational objectives. Inevitably, he went through months of soul-searching until he eventually terminated his service with Government after 35 years of service first as a restorer with the Fine Arts Museum and then as a Master in Arts in the Education Department culminating as a Head Master as well as Acting Head of the School of Art.

Having finally liberated himself from the rigours of formal employment and recovered a clear vision of his next challenges in life, Samuel Bugeja could now focus on the loves of his life – creating sculpture in wood and restoration of paintings. Born and bred in his father´s carving shop in Rabat, he found solace again in his garden shed at our Sliema home. It was full of plaster figurative models, unfinished works, grey plasticine buckets, cleaning restoration chemicals, tools and all sorts of paraphernalia. An item that was pride of place was the working bench. It was large and very heavy being made of greenheart. It had a large wooden vice as well as a smaller iron vice. An interesting feature lied on the inside of the central cupboard – old colourful Holy Pictures (santi) stuck one adjacent to the other. This bench was actually from his father’s workshop, so it had a highly sentimental value.

My father was not the most orderly of persons when it came to the daily up-keep of his studio. We used to look forward to his trips to Rome because it gave Mum the opportunity to spring clean his studio. How we relished those few days when the place would be cleaned of months old curly carved slices of wood that had formed floor carpets! It was just amazing how all chisels of such size and variety would find their way in the most awkward of nooks or crannies. Various jobs would be on-going simultaneously in the studio. There were those works that kept perennially unfinished like the wood carving of St Joseph and baby Jesus. Then there were those transitory which were addressed occasionally depending on the muse at the time. They were in various state of incompleteness. Finally, there was the restoration works that were on a fast-track. The Clients would be important people that were invariably keen to have their treasure of a painting safely back to their home.

Samuel Bugeja hated being asked by Clients for a completion date regarding their commissions. He used to give them explanations why it was not possible for him to complete a restoration within a certain time-frame. Some reasons were very plausible because it would be obvious that cleaning would be a bit of an unknown. He also depended in a way on the carpenter that had to produce the new stretching frame for the re-lining – most old paintings required re-lining. Even in those days, good carpenters had a waiting time depending on what state their order book was. Besides, they knew my father wanted an exact dimensional frame – so it was never a quick job for them. In any case, once delivered, my father and I would give the wooden frame those final touches of bevelling the face touching the canvas and the expansion grooves on all four joints.

My father’s respect and commitment was as strong as his compulsion and love of his work. He grew up with the studio just a walking distance from his family’s home. Even his important carving lessons at the Tonna’s were close by in the same village of Rabat. For him the concept of the casa-bottega (home and workshop under the same roof) was comfortable and fruitful. Many times work overlapped onto the sacred home space, invariably the dining area. My mother, a very gentle and an extremely patient person, would have no choice but to allow the work and find alternative dining arrangements.

For Samuel Bugeja the family had an even more radical element – that of maternity. There would be no life values without the love transmitted throughout the maternity process. Being deeply religious, the Madonna figure was paramount in the maternity theme. As an artist, he had to express this powerful feeling and many of his best creations are to be attributed to this affinity of the artist with this value. With time, the maternity interpretations became more classical in execution. As if the modern spontaneity of the carving chisel started to give way to the classical smoothness of the finer chiselling enabling clearer expressiveness to receptive eyes.

As a parent, my father was fair and equitable. His fathering was not characterised by much shows of affection. His work commitments kept him away from home until half past seven in the evenings because his teaching at The School of Art ended at seven in the evening. Many times Mum would have us fed and put to sleep by the time he would be back home. We were six siblings and Mum had to cope with all of us single-handedly. She did it with love because she always wanted a large family. There were times when the family problems had a telling effect, Dad and Mum never lost their composure or their magnanimity. For them we were all their siblings and equitability always prevailed.

It was just after I had completed secondary education that my father and I were doing important work on the Mdina Cathedral Polyptych of St Paul. I had options of under-graduate studies in engineering or sciences but was much undecided. I shared my thoughts with my father during the very interesting works of the Polyptych. Having been assisting my father since I was twelve years old, we had built a good relationship and I felt comfortable enough to even propose wild ideas. I had the temerity to ask him whether he would help me do graduate studies in Italy as a scientific art restorer. He had all the right contacts to place me in a good restoration centre but his advice was different. Being very equitable with all siblings, he told me that if he were to help me, the others would be equally entitled for such contributions. He said that his finances did not permit such a long period abroad with the burden that my other siblings possible demands for similar studies abroad. Also he suggested that, since the country was moving forward to an economy open to technologically oriented industry, it would make good sense to pursue an Engineering career. Being clear parental talk, I decided accordingly and never really regretted the guidance.

Samuel Bugeja’s family commitment had started early in his life. When just 19 years of age and already heavily engaged with his father Adam in various important art commissions in Churches, the Second World War broke. On Tuesday 11th June 1940, the first air raid attack by Italian bombers took place. Grandfather Adam was working on an art commission at the upper Carmelite church in Vittoriosa, one of the three harbour cities where the strong British Empire Naval Dockyard was based. Adam had already done a period of service in the Royal Air Force as a sculptor of wooden aircraft propellers. On that day the heavy bombing was horrific. Caught in the belfry of the church, he saw with his own eyes a bomb falling on the church itself and destroying the main nave reducing it to debris in a few seconds. Though the belfry suffered aftershocks, it retained its stability. Adam descended the belfry and gave a helping hand. Just on that day 56 people had died. On his return to home in Rabat, he summoned all his family and recounted to them what he had witnessed. Unfortunately, in a week’s time, the scene was totally different. Grandfather Adam developed pneumonia on the 13th June, just 2 days after the lucky escape of the bombing, and his body system began developing water soon after. On the 18th June he felt so bad that he summoned all his siblings again and to his youngest, Virgil who was just 5 years old then, he said ‘I shall be leaving you when you are still so young’ when on his death bed.

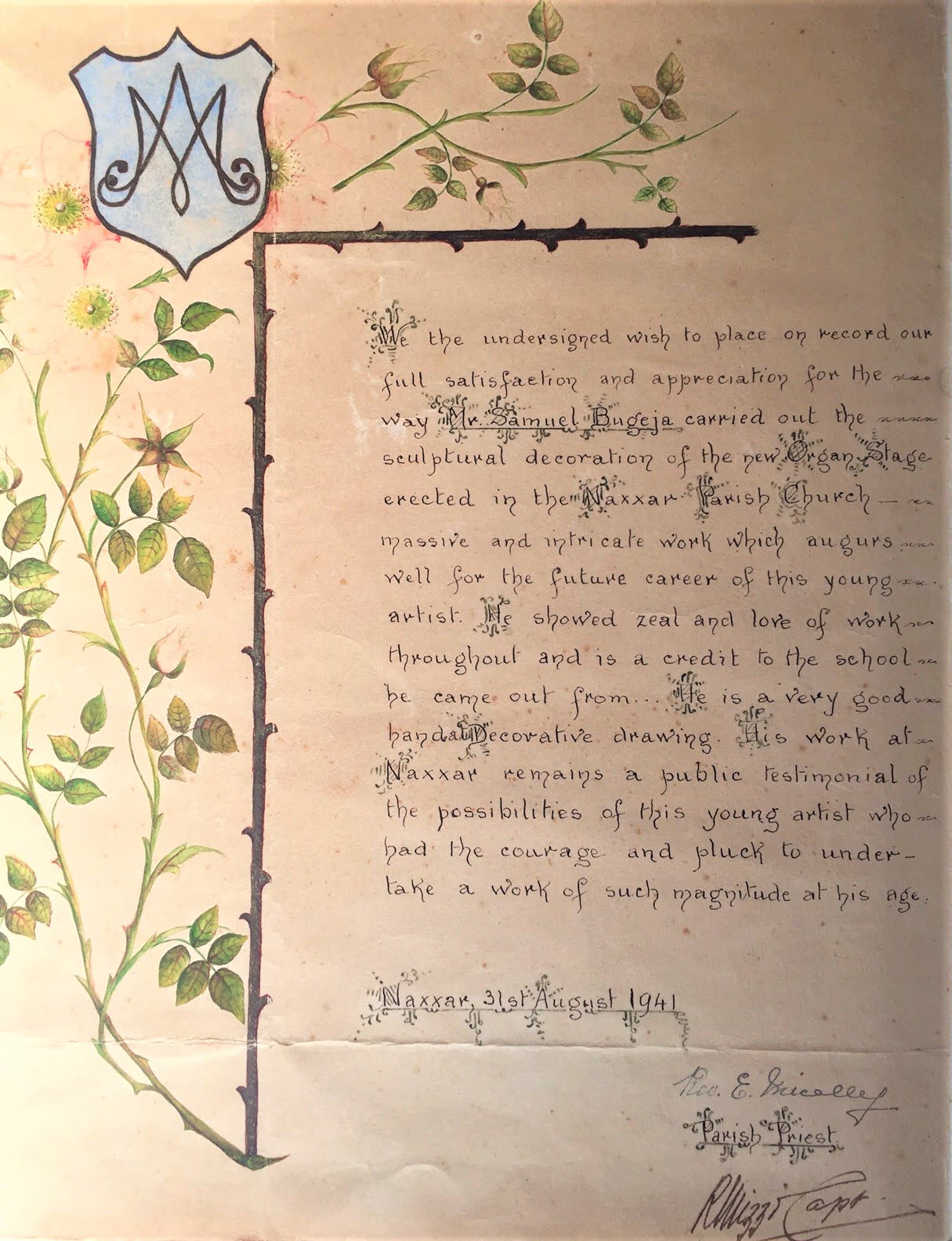

With the passing of Adam, Samuel had to take assertive decisions in the best interests of his family. First and foremost, he became the bread-winner of the family at just 19 years of age and in the process was not enrolled in the military. Secondly, he had to revisit all Clients, foremost the various Parish Priests in many villages, to confirm that they were to extend Adam’s commissions onto himself. Luckily, they all did. In particular, the Parish Priest of Naxxar stuck his neck out for a particularly difficult work of the entire organ balcony decoration above the front door of the parish church. It turned out a magnificent work of art very well acclaimed and still admired till this day. That way, the family survived the war and the later years until his siblings all got married. Samuel was their substitute father and they recognised his efforts throughout. My father rarely spoke of his supportive role during the war and post-war. I came to know of his selflessness towards his family from my aunts and uncles directly. He never boasted of his generosities whether they were done to his family or to anyone else. Those were meant to be at the lowest level of the radar so as not to be noticed by anybody.

Up to his mid-twenties, Samuel Bugeja was a secular member of a religious organisation called MUSEUM, founded by now Saint Gorg Preca. It gave my father a deeply spiritual outlook in life. Rather strict in its religious practices, the MUSEUM members were identifiable and characterised by their strong will to convey the Christian faith at the work place and where ever they were. My father was no exception – until he met my mother Helen (always known as Nellie). Their encounter was not really by chance. There was always great suspicion that it was orchestrated by two jolly buddies that shared a weakness for the bottle. Charles, my maternal grandfather, was a known personality in Rabat having been appointed to volunteer to run the Victory Kitchen in Rabat. Being a Mahoney and of British descent, the administration had no doubts on his allegiance and integrity. Having recently retired from the Navy just before the outbreak of the war, Charles had ample time to dedicate in the fair sharing of the little food available at the time. The name Victory Kitchen betrays the psychological build-up of the British during war times. At the time the Mahoney’s had sought refuge in inland Rabat from the systemic destruction taking place at Senglea, their beautiful peninsula in the middle of the Grand Harbour flanked by the two other harbour cities of Vittoriosa and Cospicua. Charles was married to Rebecca, nee Casingena, and had two siblings, Patrick and Nellie. Nellie was a little tomboyish, highly active with a ‘nice’ naughtiness when very young but was very effectively sheltered throughout her teenage years.

The other buddy was Paul Bugeja. A successful decorator Contractor, he was the brother of the demised Adam. Paul admired his nephew Samuel both professionally and even more personally. Samuel’s responsible ways, particularly towards his fatherless family, was exemplary. However, with the war nearing its end, and seeing Samuel still too reserved whilst his other younger siblings now growing into adulthood, Paul devised a clever plan to liberate his nephew. During one of the jovial regular encounters with Charles over a glass of wine, he shared his concern about Samuel. Paul went one step further – he suggested Nellie as the ideal person to entice the real Samuel out of his shell. Charles was flabbergasted. It never crossed his mind to address such issues as that of Nellie taking steps for an independent living. It was a sharp call to open one’s eyes to a reality change. Now Charles was not exactly the religious type though a diligent church goer like everybody at the time. The Samuel that was a MUSEUM member as future spouse to his only daughter might not have been the most brilliant idea considering that with Samuel around one had to be careful all the time to respect certain mind-sets – especially when the bottle may have been more than half consumed. But how could one say no to what Nellie could opt for? In any case Nellie was well past her teenage years and the time had come to release her from the surveillance she was subjected to - being a female, of course, entailed far more responsibilities than a male offspring.

Charles saw out of his depths. He waited for the right moment to disclose the matter to Rebecca, his adorable wife that had a way of handling her boisterous husband. Calm, cool and calculated she could hardly upset anybody – least of all her husband. Yet she was behind the big decisions like the timing of Charles’ retirement. Not one day more of service than the required 22 years of service for a Guiney a week pension for life. This time the decision was harder to take. Nellie was well kept and looked perfectly happy. God knows how exciting life would be that the war is nearing the end and the Mahoney family would return back to harbour life. Nellie would help in gelling the home, going off to swim right across the road in front of the house under the watchful eyes of my Grandmother Rebecca. How was this move by a dear friend Paul affect their plans. On the other hand, Nellie had reached an age when it was only natural that she prepares for her statehood. Rebecca decided that Paul’s suggestion was timely and in order. After all, Samuel was good looking and certainly would keep the family well from all aspects – he had already proved it with his mother and siblings. The match was set before the protagonists - Samuel and Nellie – even knew what was about to hit them.

Sure enough it hit them. With the right orchestration by Paul and Rebecca, luckily the chemistry was there and love blossomed. Soon enough, the time had come for Samuel to reluctantly leave the MUSEUM and Nellie to start preparations that would eventually lead her to rear a family of her own. As the big day of their marriage drew, Samuel still remained focussed on his work. Charles made sure that the wedding reception would be memorable by over-ordering the food and the booze. Paul, the mastermind of it all, said that his contribution on that day will be as the photographer. Even in those days, protocol required a professional photographer to be engaged by the groom. My father, in his typical style, just kept totally aloof. Uncle Paul had a good camera for those times and he believed to have saved the day by offering the service.